“They (EMS providers) see me, and they know that something is wrong with me. They are trying to help, but they didn’t ask me questions. It was a long ride. A lot of time to ask questions and get as much information from me so that they could help me. The whole time I was transported by EMS they never asked me.” – Fainess; labor trafficking survivor

Like Fainess, many trafficked persons interact with EMS professionals before being identified as a trafficked person. Trafficked persons are often hidden in plain sight, with their exploitation going undetected in their respective communities. Many EMS professionals have not received any training in human trafficking; however, EMS professionals are in a unique position to identify trafficked persons, gaining a view of the patient’s out-of-hospital environment not visible to most other healthcare providers. With appropriate training, EMS personnel can be well-equipped to intervene and connect these patients to the necessary community resources.

Introduction

Human trafficking is a widespread though underrecognized problem, affecting individuals locally, nationally, and globally. Human trafficking takes many forms, but it typically involves sexual or labor exploitation. The United States (U.S.) federal law defines sex trafficking as “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, obtaining, patronizing, or soliciting of a person for the purposes of a commercial sex act, in which the commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such an act has not attained 18 years of age.”1 Comparatively, under United States (U.S.) federal law, labor trafficking is defined as “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purposes of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery. “1 As many as 40.3 million people are victims of modern slavery, with 29.4 million people currently experiencing labor exploitation.2 Despite the prevalence of labor trafficking in the world, sex trafficking continues to dominate much of the conversation.3

This article aims to bring much needed attention to labor trafficking as it often goes unnoticed and under reported.3 Labor trafficking occurs in many industries including domestic work, agricultural and construction work, and fishing and factory labor.2 People of all ages, backgrounds, and genders are affected by labor trafficking, including both U.S. citizens and foreign nationals. Although certain populations are disproportionately affected by labor trafficking. Traffickers exploit vulnerable populations-such as people experiencing poverty, instability, wars, and those with a history of abuse or trauma.4 The traffickers capitalize on this vulnerability and use it as a means to control their victims. Traffickers are known to control their victims through physical, emotional, and sexual violence.4 Additionally, traffickers often confiscate any identifying documents such as passports. Lack of identification and threats of retaliation by traffickers make it difficult for trafficked persons to leave their situation or receive help.4

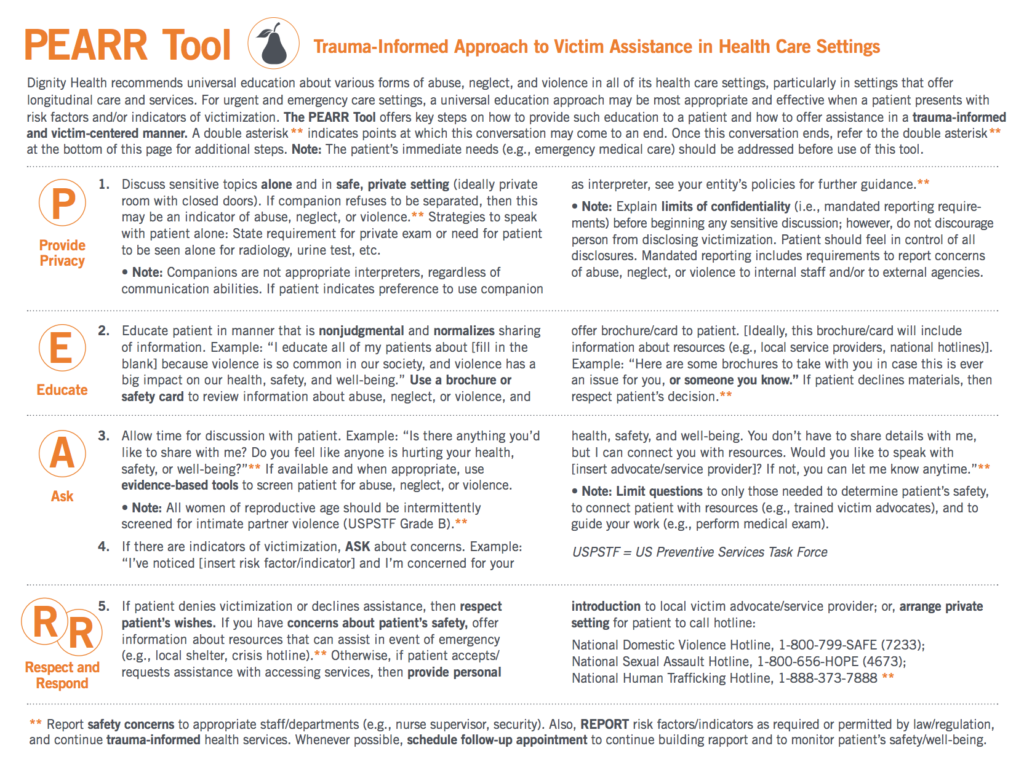

Studies suggest that up to 88% of trafficked persons accessed one or more healthcare providers while they were being trafficked.5 Of those who sought care, the most frequent point of medical contact was an emergency department (ED).5 Despite this high level of interaction with trafficked persons, less than 5% of emergency department personnel have received formal education on human trafficking.5 A 2018 study revealed that less than half of EMS providers had been educated on human trafficking.6 This gap in education presents an opportunity for emergency providers to receive formal training to better recognize and address persons experiencing trafficking and dispel common myths surrounding trafficking.6 Prior to arrival in the ED, EMS personnel may be the first healthcare providers to evaluate a labor trafficked person; this brief encounter in the isolation of the ambulance may be a trafficked person’s only chance to privately ask for help. The goal of an encounter with a potentially labor trafficked person is to educate and establish a trusting relationship. It is important that trafficked persons see the ED and other facets of healthcare as a place of refuge where resources are available.4 The goal of this article is to offer an overview for collegiate EMS providers on labor trafficking and to build confidence in providers’ ability to recognize and address patients who may be experiencing labor trafficking (Figure 1). It is essential that EMS personnel be educated on labor trafficking and how it may present in a pre-out-of-hospital setting.

Figure 1: PEARR Tool

Educating collegiate EMS providers on labor trafficking is imperative for a variety of reasons. First, some EMS providers are likely to encounter persons experiencing trafficking and need to feel confident in their ability to treat these patients. Secondly, many collegiate EMS providers are just beginning their careers in healthcare and aspire to continue in healthcare in various capacities. It is likely that collegiate EMS providers will go on to encounter potential trafficking situations on the college campuses served, but also in future clinics, hospitals, and ambulances. Early education in EMS careers is necessary as it will foster confidence in identification and treatment of people experiencing labor trafficking and help disrupt the cycle of violence that human trafficking perpetuates.

Assessing the Scene

While it is important to recognize that labor trafficking takes many forms and can present in numerous ways, certain observations should heighten suspicion that labor trafficking is occurring. The settings for labor trafficking are diverse and include, but are certainly not limited to private homes, restaurants, agricultural fields, and hotels.7 A pertinent aspect of scene size-up is prioritizing provider safety. As you arrive on scene, account for people that are on scene and may be near the patient. People who experience trafficking are often trafficked outside of their home state or country and may be unfamiliar with the language and their surroundings.8 Therefore, it is of utmost importance to employ a professional interpreter for patients to ensure that the trafficker does not serve as the interpreter. The behavior of bystanders and others on scene can offer important insight. Traffickers may begin acting defensively, refuse to leave the patient’s side, and try to speak for the patient.9 When conducting your exam and history, ensure that the patient is alone unless an in-person interpreter is needed. Assessing the patient alone can increase the likelihood that the patient will disclose concerns and ask for help.10

If there are safety concerns, it is best to request police assistance. EMS providers should also be aware of the implications of involving law enforcement on potential trafficking cases. Trafficked persons may have an innate discomfort and aversion to the presence of law enforcement personnel on a scene, especially in situations when trafficked people have been forced to commit crimes or the trafficked person is undocumented.11 Law enforcement may not be educated on labor or sex trafficking which could lead to the patient’s arrest or deportation. When law enforcement presence is needed to ensure provider safety, speak directly to on-scene officers discretely to explain one’s concern for trafficking. Further, communicating that the patient’s medical care is essential, can be helpful in limiting the patient’s interactions with law enforcement.

Due to the nature of the call, law enforcement may already be present on scene upon EMS arrival, and they may request information from the EMS provider. Laws vary from state-to-state so it is best to familiarize yourself with your respective state’s policies. While the law may permit or require disclosure of a patient’s name, any additional information should be deferred to hospital staff upon arrival. Optimally, an interprofessional protocol for managing suspected trafficking cases has been established. In the rare cases where media may be present, defer any media inquiries to your public information officer or university’s media relations office.

The History and Exam

To ensure privacy, the patient should ideally be transported alone. Even unassuming acquaintances should be left on scene if at all possible, as another trafficked person may function as a “minder” for the trafficker.12 If the patient is a non-native English speaker, when possible, have an interpreter present or access a virtual interpreter by telephone or application so that you can conduct a history and assessment in the patient’s native language. This allows for not only greater accuracy in the history and exam but can help provide some comfort for the patient as well.

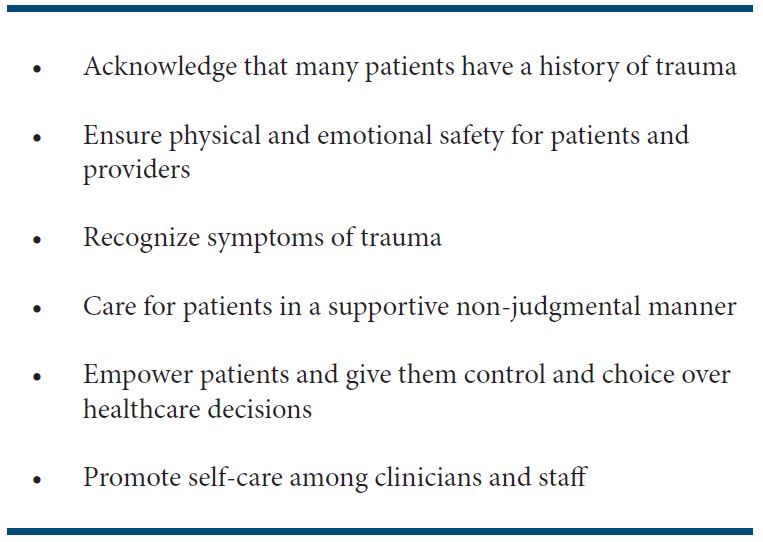

Labor trafficked persons may be reluctant to disclose their situation for fear of retribution, arrest, deportation or threats on their families. There are a variety of indicators of labor trafficking that you can look for while conducting an assessment. Victims of trafficking can display a range of responses that can vary between elusiveness and appearing withdrawn to agitation and aggressive responses due to trauma experienced. Their responses to questions may be well rehearsed and unwavering or may change repeatedly and be inconsistent. This may be frustrating for the EMS provider, but it is important to maintain a professional demeanor. A trauma-informed approach can help to not only provide some comfort to the patient, but also help to avoid re-traumatizing the patient and may bring some clarity to the patient’s responses. (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Aspects of a Trauma Informed Approach

Principles of Trauma-Informed Care

Implementing a trauma-informed approach that is victim centered is necessary when treating people who you suspect may be experiencing labor trafficking. The key tenets of trauma-informed care include acknowledging the patient’s life experiences and creating an environment that is safe—both emotionally and physically—, collaborative, trusting, empowering, and by allowing the patient to make educated choices about their care.13 While engaging with your patient, approach questions and education without judgment—an important tenet of trauma-informed care. Ask questions that can better inform you of potential victimization or exploitation the patient may be experiencing.

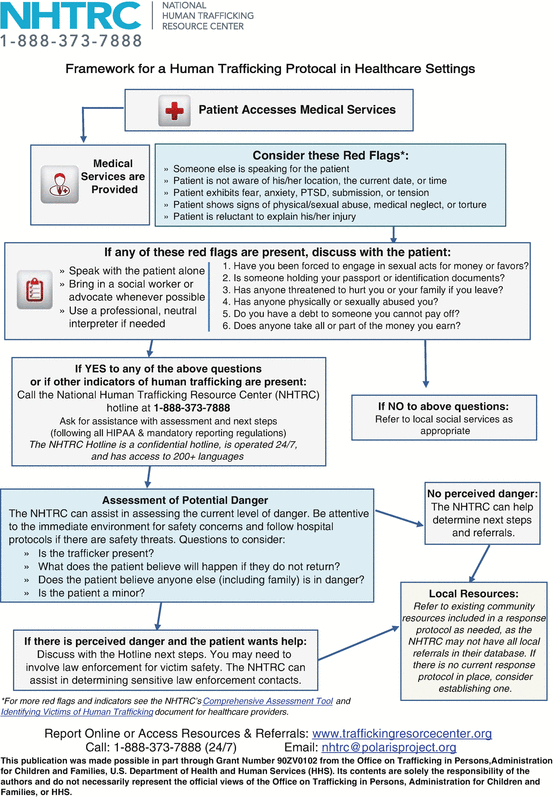

The goal of trauma-informed inquiry is to educate the patient and provide them with knowledge of resources, and not for the patient to disclose their trafficking situation. For minors, EMS providers should inform the patient of limits of confidentiality. A great resource for EMS providers to refer to regarding a trauma informed approach is the PEARR Tool, (Provide Privacy, Educate, Ask, Respect, and Respond) (Figure 1). The PEARR Tool provides an evidence-based tool for providers to address abuse, neglect, and violence, including trafficking.14 The PEARR tool can be used in conjunction with the National Human Trafficking Research Center (NHTRC) Framework for a Human Trafficking Protocol in Healthcare Settings, which includes suggestions for trafficking-specific red flags, potential questions to ask (Figure 3).

Figure 3: National Human Trafficking Resource Center Algorithm for Medical Professionals

Lastly, respect the patient’s wishes whatever they may be, and reiterate resources that are available to them if an emergency occurs or choose to seek out resources at a later date. In the situation where a trafficked person does disclose their trauma, EMS providers should share resources that are available in their community, and if EMS providers are not aware of these resources, they may call the National Human Trafficking Hotline (Figure 4). EMS Providers can utilize the National Human Trafficking Hotline to assist in identifying local, regional, and national organizations who offer anti-trafficking services. If a patient is suspected of being, or identifies as, a person being labor trafficked, EMS providers should make a concerted effort to provide brief education on the National Human Trafficking Hotline. The National Human Trafficking Hotline reports extensive statistics on human trafficking. EMS providers can look at the specific statistics for the state in which they practice to get a better idea of what labor trafficking may look like in their region.

Figure 4: National Human Trafficking Hotline Number

Physical Signs That Suggest Labor Trafficking

Above all else, the physical exam should focus on identification and management of immediate life-threatening issues. While examining the patient, certain physical findings might suggest abuse or trauma, and reveal potential trafficking situations. Common health problems reported by persons experiencing labor trafficking include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, suicide attempts, and injuries and illness related to the type of labor they perform. For example, trafficked persons may have chronic or acute heat and cold exposure or may be malnourished or dehydrated, especially if they are working and living in hazardous environmental conditions.15 Physical complaints also often include headaches, dizziness, dental problems, loss of consciousness, nausea, back pain, and fatigue.16 Any concerns or suspicions you may have that the patient is a potential trafficked person should be communicated to your partner and any other providers to whom you transfer care.

Transport

There are several considerations when transporting a patient who is suspected of experiencing labor trafficking. Domestic violence research informs us that the most dangerous time for a victim is during the separation from an abusive partner.18 Therefore, the EMS provider should keep in mind that the trafficked person has the best understanding of what will impact their safety in their trafficking situation and their relationship with their trafficker. Individuals may have several phones in their possession, which in some cases may be direct links to a trafficker, including potential GPS trafficking. The EMS provider should defer to the trafficked person’s judgment on answering incoming calls or texts on these devices, as a potential change in expected communication with a trafficker may in some situations cause retaliation against the trafficked person.17

While treating potential labor trafficked persons, it is important to remember that our job as EMS providers is to provide medical care and offer resources. If a trafficked person is not ready to leave their trafficking situation, we must respect their decisions and keep in mind we are not aware of all details regarding the situation.4 An exception to this is when minors are involved, which would usually fall under state mandatory reporting laws. In this situation, in a trauma-informed manner, the provider should follow their jurisdiction’s regulations for reporting labor trafficking.

Clothing may be inadequate or inappropriate for weather or social conditions. Consider providing a warm blanket or other items appropriate for weather conditions. When feasible, limit patient transport through high visibility or public places. For example, if the individual is being transported from a hotel, consider using a service entrance for transport to the ambulance instead of the main lobby.

Lastly, if local policy dictates a call-in to the emergency department, provide only the necessary details of the medical complaints or injuries. Avoid indicating that the person is a potentially labor trafficked person as the call-in may be a public transmission.

Hospital Interactions

It is important for EMS providers to communicate their concerns about potential trafficking to hospital staff. Proactively, EMS should engage with local hospitals and anti-trafficking service organizations to develop evidence-based, trauma-informed, multi-disciplinary practices and policies so that care can be empathetic, compassionate, and in the best interest of the patient. The organization Health, Education, Advocacy, Linkage (HEAL) Trafficking is comprised of multidisciplinary professionals dedicated to applying a public health perspective to end human trafficking and support survivors. HEAL has developed a toolkit that is an excellent resource for how to develop an interdisciplinary team to address trafficking.19

The EMS provider can play an important role in identifying concerns around labor trafficking.8 An EMS provider can share their first-hand accounts of information from the scene including work conditions. Additionally, EMS providers have had time with the patient to privately discuss medical and psychiatric concerns. It is important that this information is relayed to the hospital staff to help ensure the patient receives appropriate care.

Patients do have certain protections while in the hospital and it is important to communicate this with patients to assuage fears they may have.21 Advise hospital staff of the situation and explain the importance of limiting visitors or making the patient “anonymous” on the clinical record. In the case of a minor patient, EMS providers should take appropriate actions to file with the required agencies in their jurisdiction. This should involve integrating the appropriate authorities including law enforcement and child protective services, as applicable. Similarly, providers should file with the appropriate agency if there is suspected elder abuse. EMS providers should stay up to date with their jurisdiction’s mandated reporting requirements and know where to find the contact information of reporting agencies.

Any belongings transferred to and received by the hospital staff should be documented. In the setting of important documents, sums of money or other valuables, it is reasonable to document an itemized list.

After the call, it is important to take care of yourself and your crew members. These calls involve victims of trauma and may have a significant impact on the mental health of providers.21 Time to discuss and debrief the call may be necessary, including the involvement of additional support services that include department counselors, crisis incident debriefing, or related programs.

Discussion

Most people who experience labor trafficking seek out healthcare, especially emergency medical care, at some point while being trafficked.6 There is limited research available regarding EMS and interaction and identification of persons experiencing labor trafficking. However, research does suggest that EMS providers who receive formal education are less likely to support myths surrounding human trafficking and were able to more frequently identify human trafficking indicators.25 It is crucial that EMS providers be educated to the best extent possible on labor trafficking and confident in their abilities to serve patient populations affected by labor trafficking.

Emergency medical service providers are in a unique position to identify persons experiencing trafficking, especially labor trafficking. Details about the scene, interactions with supervisors or other employees, and working conditions are important aspects of the overall picture that may only be visible to the EMS providers on scene. Recognizing these details and raising the index of suspicion are important aspects of care. Using a trauma-informed approach during your patient interview and exam that is guided by the PEARR tool, it is important to avoid re-traumatization and give the patient a voice to discuss their concerns. An interdisciplinary approach to care that involves EMS, the hospital and social services, and potentially specialized law enforcement can help ensure that labor trafficked patients receive appropriate care in a safe environment. Access to resources like the HEAL Trafficking Toolkit or the National Human Trafficking Hotline (Figure 4) can assist individual EMS agencies in developing protocol and plans of care for individuals suspected of being trafficked.

A collegiate agency should strive to offer or attend local continuing education courses on labor trafficking to stay educated on best practices. In addition to continuing education courses, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Polaris, HEAL Trafficking, and the National Human Trafficking Hotline offer labor trafficking training courses. Consider posting helpful algorithms, numbers for local resources, and the National Human Trafficking Hotline Number around the EMS station. Furthermore, many colleges and universities have anti-trafficking coalitions and organizations that collegiate EMS agencies could partner with for education or outreach events. Collegiate EMS professionals receiving labor trafficking education early in health care careers is paramount.

References

- United States Code, 2006 Edition, Supplement 5, Title 22 – FOREIGN RELATIONS AND INTERCOURSE. Sect. 7102.

- Zimmerman C, Kiss L. Human trafficking and exploitation: A global health concern. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11):e1002437.

- David Okech, Y. Joon Choi, Jennifer Elkins & Abigail C. Burns (2018) Seventeen years of human trafficking research in social work: A review of the literature. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work. 15:2, 103-122, doi:10.1080/23761407.2017.1415177

- Barrick K, Lattimore PK, Pitts WJ, Zhang SX. When farmworkers and advocates See trafficking, but law enforcement does not: Challenges in Identifying LABOR trafficking in North Carolina. Crime, Law and Social Change. 2014;61(2):205-214. doi:10.1007/s10611-013-9509-z

- Shandro J, Chisolm-Straker M, Duber HC, et al. Human trafficking: A guide to identification and approach for the emergency physician. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2016;68(4). doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.03.049

- Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The Health Consequences of Sex Trafficking and Their Implications for Identifying Victims in Healthcare Facilities. Annals of Health Law. 2014;23(1).

- Jacobus DE. Human Trafficking: It’s All Around Us. Journal of Emergency Medical Services. July 2021.

- Kristen Bracy, Bandak Lul & Dominique Roe-Sepowitz (2021) A Four-year Analysis of Labor Trafficking Cases in the United States: Exploring Characteristics and Labor Trafficking Patterns. Journal of Human Trafficking, 7:1, 35-52, DOI: 10.1080/23322705.2019.1638148

- Dovydaitis T. Human Trafficking: The Role of the Health Care Provider. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2010;55(5):462-467. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.12.017

- Leslie J. Human trafficking: Clinical assessment guideline. Journal of Trauma Nursing. 2018;25(5):282-289. doi:10.1097/jtn.0000000000000389

- Patel RB, Ahn R, Burke TF. Human trafficking in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(5):402-404.

- Clawson HJ, Dutch N, Cummings M. Law enforcement response to human trafficking and the implications for victims in the United States, 2005. ICPSR Data Holdings. 2011. doi:10.3886/icpsr20423

- Altun S, Abas M, Zimmerman C, Howard LM, Oram S. Mental health and human trafficking: Responding to survivors’ needs. BJPsych International. 2017;14(1):21-23. doi:10.1192/s205647400000163x

- Kuzma EK, Pardee M, Morgan A. Implementing patient-centered trauma-informed care for the perinatal nurse. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 2020;34(4). doi:10.1097/jpn.0000000000000520

- Alhajji L, Padilla V, Mavrides N, Potter JN. Helping survivors of human trafficking. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):51-52. doi:10.12788/cp.0093

- Stoklosa H, Kunzler N, Ma ZB, Luna JC, de Vedia GM, Erickson TB. Pesticide exposure and heat exhaustion in a migrant agricultural worker: A case of labor trafficking. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2020;76(2):215-218. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.03.007

- Kiss L, Zimmerman C (2019) Human trafficking and labor exploitation: Toward identifying, implementing, and evaluating effective responses. PLOS Medicine 16(1): e1002740. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002740

- Latonero M. Technology and human trafficking: The rise of mobile and the diffusion of technology-facilitated trafficking. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2012. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2177556

- Block CR. How can practitioners help an abused woman lower her risk of death? PsycEXTRA Dataset. 2003. doi:10.1037/e569102006-002

- Stoklosa, Hanni, Aimee Grace, Nicole Littenberg. “Medical Education on Human Trafficking.” AMA Journal of Ethics. 17. no. 10 (2015): 914-921.

- United States of America: Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 [United States of America], Public Law 106-386 [H.R. 3244], 28 October 2000

- Bercier, Melissa Lynn, “Interventions That Help the Helpers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventions Targeting Compassion Fatigue, Secondary Traumatic Stress and Vicarious Traumatization in Mental Health Workers” (2013). Dissertations. Paper 503

- Dignity Health HEAL Trafficking and Pacific Survivor Center, 2020. Dignity Health | Using The PEARR Tool. [online] Dignityhealth.org. Available at: https://www.dignityhealth.org/hello-humankindness/human-trafficking/victim-centered-and-trauma-informed/using-the-pearr-tool

- Recognizing Human Trafficking. [Available from: https://polarisproject.org/human-trafficking/labor-trafficking.]

- Donnelly EA, Oehme K, Barris D, Melvin R. What do ems professionals know about human trafficking? an exploratory study. Journal of Human Trafficking. 2018;5(4):325-335.

Author & Article Information

Lauren N. Wilson, MA, EMT is a recent graduate of Arizona State University who served with Arizona State University EMS. Stephen P. Wood, MS, ACNP, EMT is the Director of Advanced Practice Providers in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Scott A. Goldberg, MD, MPH is an Emergency Physician in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. Aislinn Foltz-Colhour, EMT is a former Hotline Supervisor with the National Human Trafficking Hotline at Polaris. Carin M. Van Gelder, MD, Emergency Physician at St. Vincent’s Medical Center in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Hanni Stoklosa, MD, MPH is the Executive Director, HEAL Trafficking and Emergency Physician in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

Author Affiliations: From Arizona State University EMS – in Tempe, AZ (L.N.W). From Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center – in Boston, MA (S.P.W.). From Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital – in Boston, MA (S.A.G.). From National Human Trafficking Hotline at Polaris (formerly) – in Washington, DC (A.F.). From St. Vincent’s Medical Center – in Bridgeport, CT (C.M.V.). From Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital – in Boston, MA (H.S.).

Address for Correspondence: Lauren N. Wilson | Email: lauren.noelle.wilson@asu.edu

Conflicts of Interest/Funding Sources: By the JCEMS Submission Declaration Form, all authors are required to disclose all potential conflicts of interest and funding sources. All authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest. All authors declared that they did not receive funding to conduct the research and/or writing associated with this work.

Authorship Criteria: By the JCEMS Submission Declaration Form, all authors are required to attest to meeting the four ICMJE.org authorship criteria: (1) Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND (2) Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND (3) Final approval of the version to be published; AND (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Submission History: Received July 6, 2020; accepted for publication Oct 11, 2021

Published Online: February 25, 2022

Published in Print: February 25, 2022 (Volume 5: Issue 1)

Reviewer Information: In accordance with JCEMS editorial policy, Case Reports undergo double-blind peer-review by at least two independent reviewers. JCEMS thanks the anonymous reviewers who contributed to the review of this work.

Copyright: © 2022 Wilson, Wood, Goldberg, Foltz-Colhour, Van Gelder & Stoklosa. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The full license is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Electronic Link: https://doi.org/10.30542/JCEMS.2022.05.01.03